Canterbury Archbishop’s Biological Dad revealed

Justin Welby is reinventing how to be

a church leader in a sceptical world

Archie Bland, in the Guardian, UK, April11,2016

After the revelations about his parentage, the Archbishop of Canterbury showed himself to be humane and generous, not an infallible messenger of an absolute truth

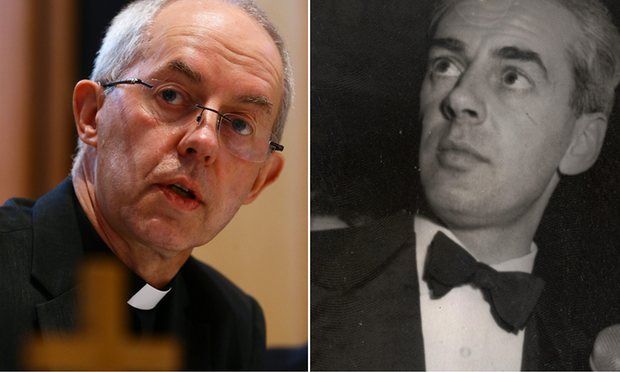

Justin Welby and his biological father, Anthony Montague Browne. Composite: Rex Features

(Note; The two-year synodal study of Catholic families has revealed how complicated and messy at times are human and family relationships. The late revelation of the biological paternity of the Anglican Archbishop was both a shock and eye opener to the public and to the spiritual leader. It only highlights that human relations and family life are not all joy and love, that realities are often far different from the ideals. In a world of many cover-ups in the Catholic church (Priestly Pedepholia) what is admirable and exemplary about the Archbishop was he underwent a DNA test and told the public, especially the flock he was leading that he was the child of an illicit relation his mother had with Anthony Montague Browne, a secretary to Winston Churchil. It reminds one of Annadurai, the famous public speaker CM of Chennai. At one of his public speeches he was asked point blank from the audience: “Who is your father?” Annadurai had the honesty, maturity and courage to face the questioner head on with the reply: “I was born for money.” Such examples are rare in history, whether in religion or in politics. After all what is Christianity, if not bearing witness to truth, even when it is bitter? Wait for a detailed report from Guardian on Montague Browne and Archbishop’s mother. james kottoor, editor)

Over the weekend, Christians were given two irreducibly modern versions of leadership on familial love. Pope Francis published Amoris Laetitia(The Joy of Love), his vision for the Catholic church’s teaching on romantic and parental relationships, which sought to present the church’s traditional view of abortion, homosexuality and divorce in a context that emphasised compassion, and an acknowledgement of complexity above the stern absolutes that we’re used to.

No one should mistake Amoris Laetitia for a piece of cuddly revisionism. But in an institution so intractably absolute as the Catholic church, the tonal and practical steps that the document does take, omitting the usual description of gay relationships as “intrinsically disordered” and encouraging clerics to reach their own conclusions on communion divorcees, are no small thing. Within the straitjacket of his position, Pope Francis appears to be wiggling his hands around as much as possible.

When the news about the Archbishop of Canterbury’s parentage broke, though, the limits on the force of any such document were made abundantly clear. Justin Welby explained that he had recently learned his father was not Gavin Welby, the whisky salesman married to his mother, but Sir Anthony Montague Browne, private secretary to Winston Churchill, with whom his mother had had what was rather primly referred to as a “liaison” shortly before her marriage.

The proof of this had not come about by any involuntary tabloid sting, but because Welby had agreed to the Daily Telegraph’s suggestion of a DNA test, and then to speak to the newspaper about it.Welby’s response was extraordinary for its unabashed acceptance of the compromises that decorate most human relationships, and for his insistence that the news could not define him.

“Although there are elements of sadness,” he said in a statement, “and even tragedy in my father’s case, this is a story of redemption and hope from a place of tumultuous difficulty and near despair in several lives … I know that I find who I am in Jesus Christ, not in genetics, and my identity in him never changes.”

The papal document will, of course, have more significant practical ramifications. But the archnishop’s explanation of his family history surely resonates more deeply with more people, and provides a powerful example of the role that even an avowed atheist might hope for religious leaders to take today.

Neither the archbishop nor Pope Francis could easily be confused with Peter Tatchell, but within the practical and political limits that their lumbering institutions present, both men seem to have recognised that they need to do more to show that Christianity is not a magisterial rulebook designed to tell you why you’re a monster, but rather a merciful companion in life’s hardest times.

And while that emphasis is of some value in a document that in the end very few people will read and which leaves the church’s sternest diktats in place, it could hardly be more powerfully presented than in Welby’s testimony.

He has, after all, been through very much worse than this: when one considers the tragic death of his baby daughter in a car crash in 1983, the idea that anyone could view something so relatively trivial as a sexual indiscretion as a catastrophe begins to seem absurd. His personal generosity – to his flock and to his family – reminds us that, while personal troubles aren’t exactly a qualification for moral leadership, they are bound to make its practice more meaningful to the people who need it most.

Religious leaders are too often comfortable with being presented as the voice of God; infallible messengers of a ludicrously absolute truth that may bring misery to those who seek to follow it. Justin Welby’s story, messy and ordinary as it is, also gives Anglicans, Catholics, and other faiths alike a glimpse of a model that is surely more likely to sustain their relevance in an ever-more sceptical world: one which understands that, in the end, the influence of their commandments will always be dictated by the voice in which they are spoken.

***************************